As a proponent of the Move programming language, every time I promote Move to developers, I always encounter the same question: What are the advantages of Move? Why Move?

Introducing your favorite topic to an outsider, you always face the same kind of questions. However, this question is not easy to answer. If we list the pros and cons one by one, there will always be people who question them. After all, the ecosystem of a new language is not yet mature, and the choice can only be based on its potential. Let me make a statement: Move has the most potential of any programming language to build an ecosystem like Solidity, and even to surpass Solidity.

Target audience: Developers who are interested in the technology of the blockchain field. This article hopes to explain the current challenges faced by smart contracts and provide some solutions of Move in a simple way, with minimal use of code, so that readers who do not understand programming languages can also roughly understand it. Feedback from readers is appreciated.

This article was written in May 2022, when Move was just emerging and there was no current scale. I translated and reposted it here,original link (opens in a new tab).

Two Paths of Smart Contracts

If we go back a few years, there were mainly two ways to support Turing-complete smart contracts on new public chains.

One is to tailor existing programming languages and run them on universal virtual machines such as WASM. The advantage of this approach is that the current programming languages and WASM virtual machine ecosystem can be reused.

The other is to create a new smart contract programming language and virtual machine from scratch, like Solidity and Move.

At that time, many people were actually not optimistic about the Solidity&EVM ecosystem. They thought that Solidity was only useful for token issuance, had poor performance, weak tools, and was like a toy. The goal of many chains was to enable developers to use existing languages for smart contract programming, and the first path was more favored. There were few new public chains that directly copied Solidity&EVM.

However, after several years of development, especially with the rise of DeFi, people suddenly found that the Solidity ecosystem was different. The smart contract ecosystem that took the first path did not grow up. Why? I will summarize a few reasons.

- The blockchain's program runtime environment is very different from the operating system's program runtime environment. If we discard the libraries related to system calls, file IO, hardware, network, concurrency, and consider the execution cost on-chain, the amount of libraries that can share with smart contracts is very limited.

- The first solution theoretically supports many languages, but in reality, programming languages with a runtime compiled into a virtual machine similar to WASM result in very large files, making it unsuitable for use in blockchain scenarios. The only ones that can be used are mainly C, C++, Rust, etc. without a runtime. The learning curve of these languages is not lower than the cost of smart contract programming languages like Solidity. Supporting multiple languages at the same time may lead to the fragmentation of early ecosystems.

- Each blockchain has a different state handling mechanism, so even if they all use WASM virtual machines, smart contract applications on each blockchain cannot be directly migrated, and they cannot share a common programming language and developer ecosystem.

For application developers, they directly face smart contract programming languages, the basic libraries of programming languages, and whether there are reusable opensource libraries. The security of DeFi requires smart contract code to be audited, and every line of audited code represents money. If developers can slightly modify and copy existing code, they can reduce audit costs.

Now it seems that although Solidity took a seemingly slow path, it actually built its ecosystem faster. Many people now believe that Solidity&EVM is the endpoint of smart contracts, and many chains are beginning to support or port Solidity&EVM.

At this point, a new smart contract programming language needs to prove that it has stronger ecosystem building capabilities to convince people to pay attention to and learn to use it.

So the new question is, how does one measure the ecosystem building capabilities of a programming language?

Programming language's ecosystem building ability

The ecosystem building ability of a programming language refers to its code reuse capability, which mainly manifests in two aspects:

- The dependency method between modules of the programming language.

- The combination method between modules of the programming language.

"Composability" is a feature touted by smart contracts, but in fact, programming languages all have composability. We invented interfaces, traits to make composition more convenient.

Let's talk about the dependency method first.

Programming languages typically implement dependencies through three methods:

- Using static libraries, which statically link dependencies during compilation and package them in the same binary.

- Using dynamic libraries, which dynamically link dependencies at runtime. The dependencies are not included in the binary, but must be deployed on the target platform in advance.

- Depending on remote procedure calls (RPC) at runtime. This refers to various APIs that can be called remotely.

Methods 1 and 2 are generally used in the common library. Common libraries are usually stateless, as it is difficult to assume how an application handles state, such as which file to write to or which database table to store in.

This kind of call occurs in the same process and method call context, sharing the call stack and memory space, with no strong isolation (or weak isolation), and requires a trusted environment.

Method 3 actually calls another process or a process on another machine, communicating with each other through messages, and each process is responsible for its own state. Therefore, state dependencies can be provided, and the call also has security isolation.

Each of these three methods has its pros and cons.

Method 1 includes the dependency libraries in the final binary, which has the advantage of not requiring the target platform environment, but the disadvantage of producing a larger binary.

Method 2 has the advantage of producing a smaller binary, but requires a runtime environment.

Method 3 can build cross-language dependency relationships and is generally used in scenarios involving cross-service or cross-organization collaboration. To facilitate developer calls, it is generally simulated as a method call through SDK or code generation.

In the history of technology, many programming languages and operating system platforms have spent a lot of effort trying to bridge the gap between remote and local calls, trying to achieve seamless remote calling and composition.

Just to mention a few famous technical terms, such as COM (Component Object Model), CORBA, SOAP, REST, etc., all of which are used to solve these problems. Although the dream of seamless call has been shattered, and everyone finally relied on engineers to manually connect interfaces, splicing together the entire Web2 service, the dream is still alive.

Smart contracts have brought new changes to the dependency methods between applications.

Changes brought by Smart Contracts

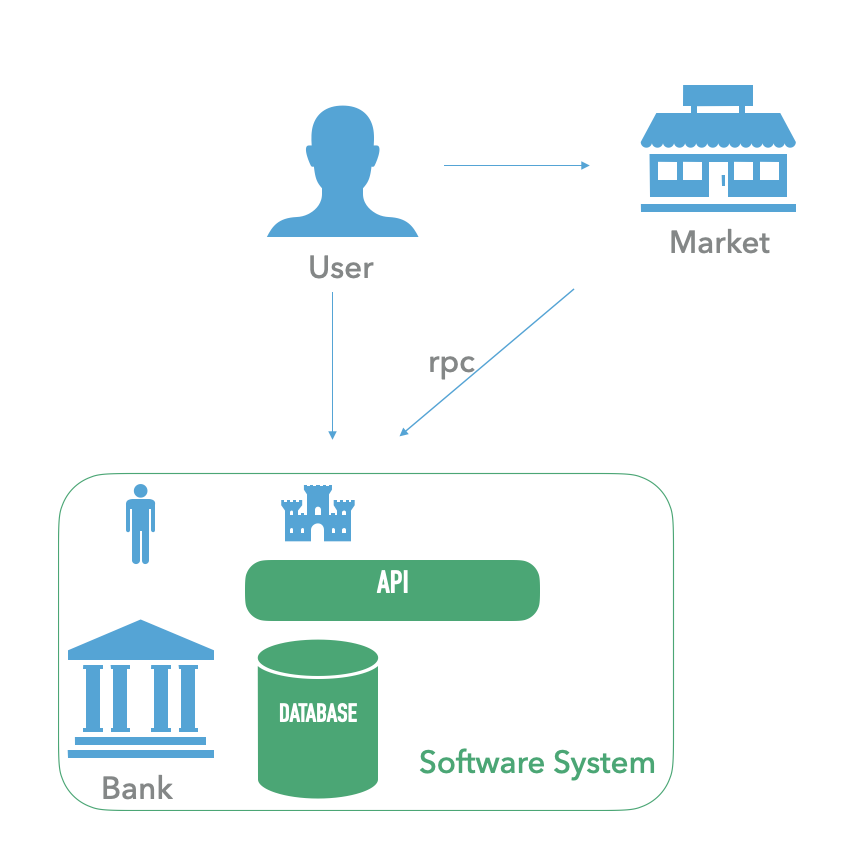

The dependency between traditional enterprise applications can be illustrated by the following figure:

- Systems are connected through various RPC protocols, linking services running on different machines.

- Various technical and manual "walls" are put in place between machines to ensure security.

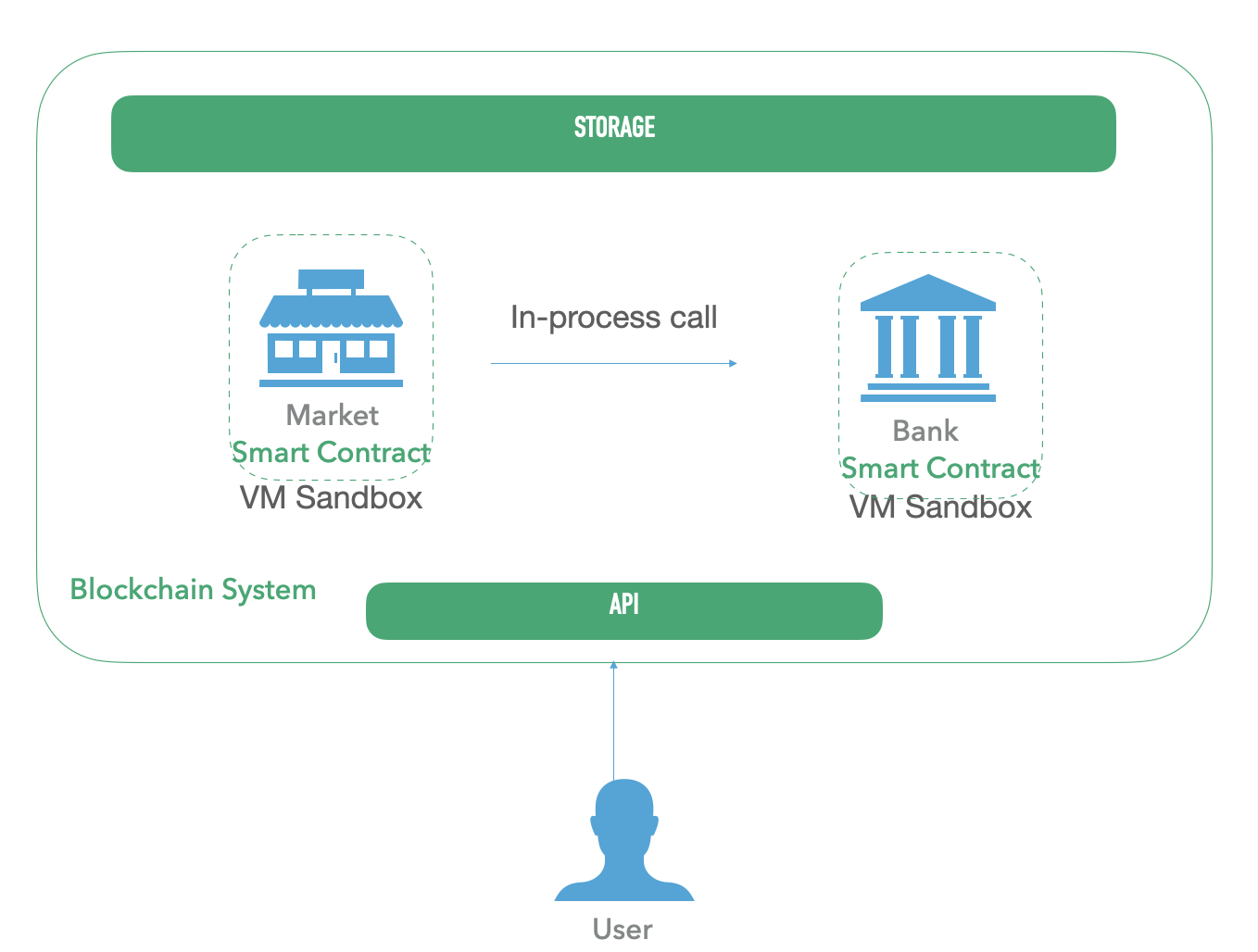

In contrast, the execution environment of a smart contract is a sandbox environment constructed by the node of the blockchain. Multiple contract programs run in different virtual machine sandboxes within the same process, as shown in the following figure:

- Calls between contracts are calls between different smart contract virtual machines within the same process.

- Security depends on the isolation between smart contract virtual machines.

Using Solidity as an example, Solidity contracts (modules indicated as contract) declare their functions as public, and then other contracts can directly call the contract through this public method.

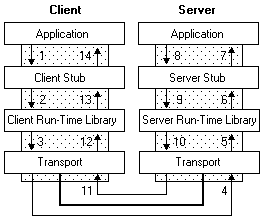

An RPC call process is shown in the following figure:

Image source https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/rpc/how-rpc-works (opens in a new tab)

In fact, the blockchain takes over all the communication processes between the Client and Server in the above figure, automatically generates stubs, implements serialization and deserialization, and makes developers feel that remote calls are just like local method calls.

Of course, there is no silver bullet in technology, and new solutions always bring new challenges that need to be addressed.

The Dependency Challenge of Smart Contracts

Through the previous analysis, we understand that the invocation between smart contracts is actually a method similar to remote invocation. But what if we want to call dependencies through libraries?

In Solidity, a module indicated as library is equivalent to a static library and must be stateless.

The dependency on a library will be packaged into the final contract binary during compilation.

This creates a problem: if the contract is complex and has too many dependencies, the compiled contract will be too large to be deployed. However, if it is divided into multiple contracts, it will not be possible to directly share the state, and internal dependencies will become dependencies between remote services, increasing the call cost.

Can we use the second solution, loading dynamic libraries? For example, most contracts on Ethereum depend on the SafeMath.sol library, and each contract contains its binary. Since the bytecode is on the chain, why can't it be directly shared?

Therefore, Solidity provides the delegatecall method, similar to the dynamic linking library solution, which loads the bytecode of another contract into the context of the current contract, allowing the other contract to directly read and write the state of the current contract. But this requires two things:

- The calling and called parties must have a completely trusted relationship.

- The state of the two contracts must be aligned.

Those who aren't smart contract developers may not understand this issue. If you are a Java developer, you can think of each Solidity contract as a Class. Once deployed, it runs as a singleton Object. If you want to load a method from another Class at runtime to modify the properties of the current Object, the fields defined in these two Classes must be the same, and the newly loaded method is equivalent to an internal method, with full access to the internal properties of the Object.

This limits the use case and reuse of dynamic linking, and it is now mainly used for internal contract upgrades.

Because of the above reasons, it is difficult for Solidity to provide a rich standard library (stdlib) like other programming languages, to be deployed on the chain in advance and depended on by other contracts. It can only provide a few limited precompiled methods.

This has also led to the inflation of EVM bytecode. Data that could have been obtained from the state via system contract code was forced to be implemented through virtual machine instructions. For example, instructions such as BLOCKHASH, BASEFEE, and BALANCE, the programming language itself does not need to know the chain-related information.

This problem is encountered by all chains and smart contract programming languages. Traditional programming languages did not consider security issues within the same method call stack, and when moved to the chain, they can only rely on static dependencies and remote dependencies to solve the dependency relationship. Generally, even a delegatecall solution like Solidity is difficult to provide.

So how can we achieve a way of calling between smart contracts similar to dynamic library linking? Can the invocation between contracts share the same method call stack and directly pass variables?

This approach brings two security challenges:

- The security of the contract's state must be isolated through the security of the programming language itself, rather than relying on the virtual machine for isolation.

- The cross-contract variable transfer needs to ensure safety and prevent arbitrary discarding, especially for variables that express asset types.

State Isolation for Smart Contracts

As mentioned earlier, a smart contract actually executes code from different organizations in the same process. Therefore, it is necessary to isolate the contract's state (which can be simply understood as the results generated when the contract is executed, which need to be saved for use in the next execution) to avoid security problems caused by allowing one contract to directly read and write the state of another contract.

The isolation solution is actually easy to understand - give each contract an independent state space. When executing a smart contract, the current smart contract's state space is bound to the virtual machine, which means that the smart contract can only read its own state. If another contract needs to be read, it needs to use the contract invocation mentioned earlier, which is actually executed in another virtual machine.

However, this isolation is not enough when using dynamic libraries for dependencies. Because another contract is running in the execution stack of the current contract, we need language-level isolation rather than virtual machine isolation.

In addition, the state space isolation based on contracts also brings up the issue of state ownership. In this case, all states belong to the contract, and there is no distinction between the public states of contracts and the personal states of users. This makes it difficult to calculate state fees, and in the long run, there will be a problem of state explosion.

So how can we achieve state isolation in smart contract languages? The idea is actually simple - based on types.

- Utilize the visibility constraints that programming languages provide for types, a feature that most programming languages support.

- Utilize the mutability constraints that programming languages provide for variables. Many programming languages differentiate between mutable and immutable references, such as Rust.

- Provide external storage based on types as keys, limiting the current module to only read external storage using the types it defines as keys.

- Provide the ability to declare copy and drop for types in programming languages, ensuring that asset-like variables cannot be copied or discarded.

Move language uses the above solutions, with points 3 and 4 being unique to Move. This solution is also easy to understand because if we cannot give each smart contract program a separate state space at the virtual machine level, then using types for state isolation is a relatively easy-to-understand method because types have clear ownership and visibility.

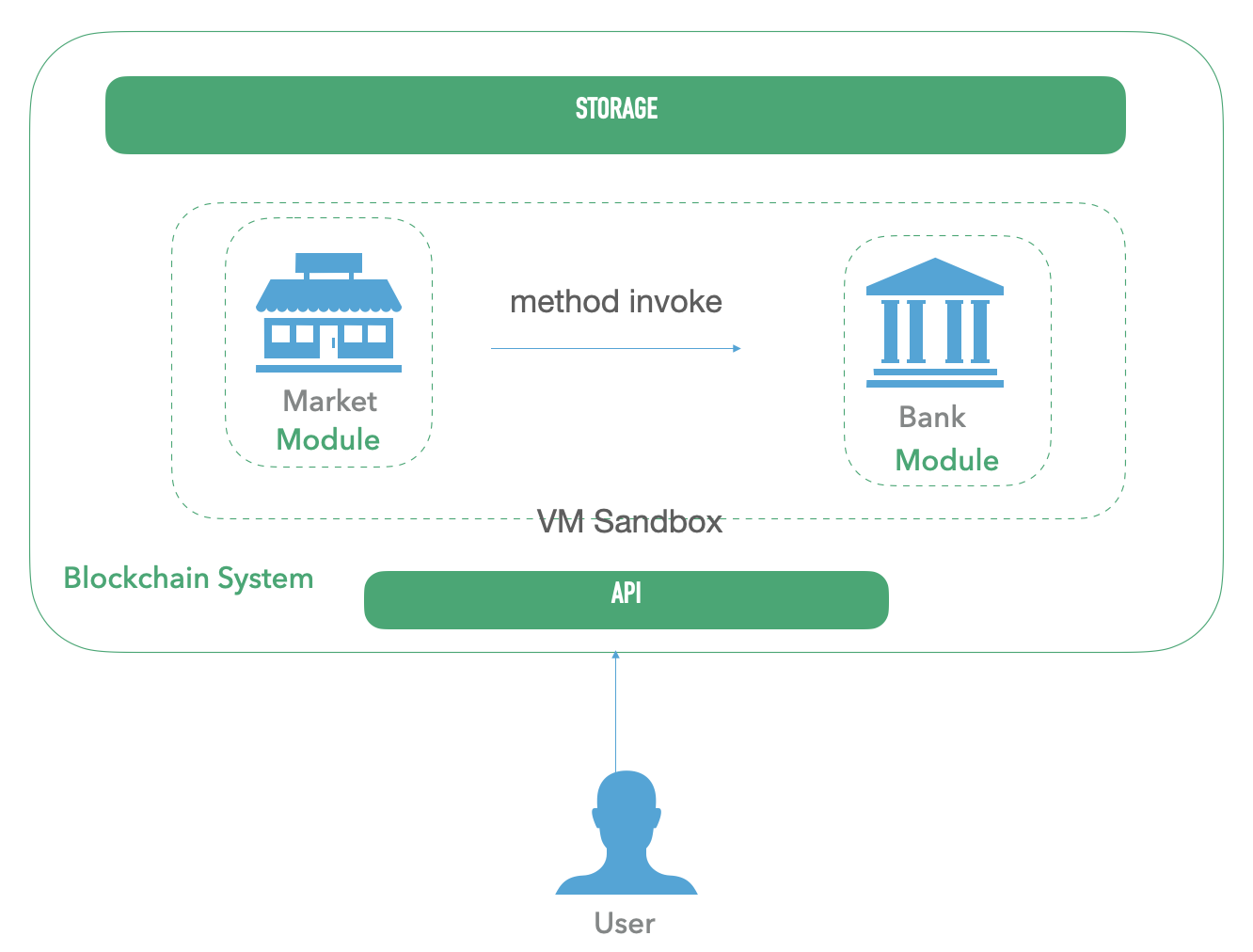

In Move, the smart contract invocation between different organizations and programs is as shown in the following figure:

Different programs from different organizations are combined into the same application and run through dynamic libraries, sharing the same memory world of the programming language. Organizations can pass messages, also pass references and resources to each other. The rules and protocols for interaction between organizations are only constrained by the rules of the programming language. (The definition of resources will be described later in the article.)

This change brings several advantages:

- The programming language and the chain can provide a rich library that can be deployed on the chain in advance(called XChain-Framework). Applications can directly depend on and reuse it, without including the std library in their own binaries.

- Since the code of different organizations is in the same memory world state of the same programming language, richer and more complex combination methods can be provided. This topic will be described in detail later.

The dependency mechanism of Move, while similar to the dynamic library pattern, also utilizes the state-managing feature of the chain, bringing a new dependency pattern to programming languages.

In this pattern, the chain serves both as the execution environment for smart contracts and the binary repository for smart contract programs.

Developers can freely combine smart contracts on the chain through dependencies to provide a new smart contract program, and this dependency relationship is traceable on the chain.

Of course, Move is still in its early stages, and the capabilities provided by this dependency mechanism have not been fully utilized, but the prototype has emerged.

It can be imagined that in the future, incentive mechanisms based on dependency relationships will definitely appear, as well as new open source ecosystems built on this incentive model.

Next, we will continue to discuss the issue of "composability".

Composability of Smart Contracts

Composability between programming language modules is another important feature of building a programming language ecosystem. It can be said that it is the composability between modules that needs dependencies, and different dependency methods provide different composability.

According to the analysis of the dependency methods above, when discussing the composability of smart contracts in the Solidity ecosystem, it actually mainly refers to the combination of contract, not the combination of library. As mentioned earlier, the dependency between contracts is a type of dependency similar to remote invocation. What is actually passed between them is a message, not a reference or resource.

Here, the term resource is used to emphasize that this type of variable cannot be copied or discarded arbitrarily within the program, which is a feature of linear types that is not yet popular in programming languages.

Linear types come from linear logic, and linear logic itself is designed to express logic related to resource consumption that classical logic cannot express.

For example, if we have "milk," we can infer "cheese" logically, but we cannot express resource consumption or the logic that X units of "milk" can produce Y units of "cheese". Therefore, linear logic and linear types were developed, which can be applied in programming languages.

The first resource to be managed in programming languages is memory. Therefore, one application scenario of linear types is to track the use of memory to ensure that memory resources are properly reclaimed, such as in Rust. However, if this feature is widely promoted, we can simulate and express any type of resource in the program.

So why is it important to pass resources during composition? Let's first understand the current composition method based on Interface, which is the composition method used by most programming languages, including Solidity.

The most important thing when combining multiple modules is to agree on the functions to be called, as well as the parameter and return value types of the functions, which are generally called the "signature" of the function. We usually use Interface to define these constraints, but the specific implementation is left to each party.

For example, the ERC20 Token that people often talk about is an Interface that provides the following methods:

function balanceOf(address _owner) public view returns (uint256 balance)

function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) public returns (bool success)The definition of this interface includes a method for transferring Token to a specific address and a method for checking the balance, but there is no direct method for withdrawing Token. This is because in Solidity, tokens are a service rather than a type. Here is a similar method defined in Move:

module Token{

struct Token<TokenType>{

value: u128,

}

}

module Account{

withdraw(sender: &signer, amount):Token<STC>;

deposit(receiver: address, token: Token<STC>);

transfer(sender, receiver, amount);

}As you can see, Token is a type, and a Token object can be withdrawn from an account. Some may ask, what is the significance of doing this?

We can compare the two methods of combination using a common analogy. A Token object is similar to cash in everyday life. When you want to buy something from a store, there are two payment methods:

- The store and the bank have an interface connection to an electronic payment system. When you pay, you initiate a request to the bank to transfer the funds to the store.

- You withdraw cash from the bank and pay at the store. In this case, the store does not need to connect to the bank interface in advance, it just needs to accept this type of cash. As for whether the store locks the cash in a safe or continues to deposit it in the bank after receiving it, that is up to the store to decide.

The second type of combination method can be called a resource-based combination method. We can refer to the resource that flows between contracts of different organizations as "free state".

The resource-based combination method is more similar to the combination method in the physical world, such as CDs and players, various machine components. This combination method is not in conflict with the interface-based combination method. For example, if multiple exchanges (swap) want to provide a unified interface for external integration, using the interface-based combination method is more appropriate.

There are two key advantages of the resource-based composition:

- It can effectively reduce the nesting depth of interface-based composition. (flash loans is a good example for this but considering that some readers may not be familiar with the background of flash loans, I won't elaborate on it here).

- It can clearly separate the definition of resources from the behavior based on resources.

A typical example is the NFT for soulbound. The concept of NFT for soulbound was proposed by Vitalik. It is intended to use NFT to express a certain identity relationship, which should not be transferable, such as graduation certificates, honor certificates, etc.

However, the NFT standards on ETH are all interfaces, such as several methods in ERC721:

function ownerOf(uint256 _tokenId) external view returns (address);

function safeTransferFrom(address _from, address _to, uint256 _tokenId) external payable;If you want to extend new behaviors, such as binding, you need to define new interfaces. This will also affect old methods, such as transferring NFT. If the NFT has been soulbound, it cannot be transferred, which will inevitably bring about compatibility issues. Even more challenging is the scenario where it is initially allowed to transfer but becomes untransferable after binding, such as some game props.

But if we think of NFT as an item, the item itself only determines how it is displayed and what properties it has. Whether it can be transferred should be encapsulated at the upper level.

For example, the following NFT defined using Move is a type.

struct NFT<NFTMeta: copy + store + drop, NFTBody: store> has store {

creator: address,

id: u64,

base_meta: Metadata,

type_meta: NFTMeta,

body: NFTBody,

}Then we can imagine the upper-level encapsulation as different containers with different behaviors. For example, when NFT is placed in a personal gallery, it can be taken out, but once it is placed in some special container, it requires other rules to be met before it can be taken out, which realizes "binding".

For example, Starcoin's NFT standard implements a container for soulbound NFT called IdentifierNFT: (The code is simplified)

/// IdentifierNFT contains an Option<NFT> which is empty by default, it is like a box that can hold NFTs

struct IdentifierNFT has key {

nft: Option<NFT<T>>,

}

/// Users initialize an empty IdentifierNFT under their own account through the `accept` method

public fun accept<T>(sender: &signer);

/// Developers grant the NFT to receiver by using the MintCapability, and embed the NFT into the IdentifierNFT

public fun grant_to<T>(_cap: &mut MintCapability, receiver: address, nft: NFT<T>);

/// Developers can also take out the NFT in the IdentifierNFT of `owner` using the BurnCapability

public fun revoke(_cap: &mut BurnCapability, owner: address): NFT<T>;The NFT in this box can only be granted or revoked by the issuer of the NFT, while the user can only decide whether to accept it or not. For example, in the case of a graduation certificate, the school can issue and revoke it. Of course, developers can also implement other rules for the container, but the NFT standard is unified. For readers interested in the specific implementation, please refer to the link at the end of the article.

This section illustrates a new way of combining things in Move based on linear types. However, the advantage of language features alone cannot naturally bring about an ecosystem of programming languages; there must also be application scenarios. Let's continue to discuss the application scenario expansion of the Move language.

Expanding the Application Scenarios of Smart Contracts

Move, originally designed as the smart contract programming language for the Libra blockchain.

At the time, we were designing the architecture of Starcoin, and considering that Move's features aligned perfectly with Starcoin's goals, applied Move to the public chain scenario.

Later on, after the Libra project was abandoned, several public chain projects were incubated to explore different directions:

- MystenLabs' Sui introduced immutable states, attempting to implement a UTXO-like programming model in Move.

- Aptos explored the parallel execution of transactions on Layer1 and high performance.

- Pontem attempted to bring Move into the Polkadot ecosystem.

- Starcoin explored the layered scaling solution of Layer2 and even Layer3.

Meanwhile, the original Move team at Meta (Facebook) is attempting to run Move on Evm, although this may result in losing the feature of transferring resource between contracts, it helps to expand the Move ecosystem and merge it with the Solidity ecosystem.

Currently, the Move project has been spun off as a completely community-driven programming language. It faces several challenges:

- How to find the greatest common denominator between the requirements of different chains to ensure the language's universality.

- How to allow different chains to implement their own specific language extensions.

- How to share basic libraries and application ecosystems among multiple chains.

These challenges are also opportunities, but they conflict with each other, requiring trade-offs and the Move community needs to find a balance in development progress. No language has attempted this kind of endeavor before. This balance can ensure that Move can explore more application scenarios, not just those tied to blockchain.

In this regard, one problem that Solidity/EVM has it that they are entirely tied to the chain, and running EVM requires simulating a chain environment. This limits Solidity from expanding to other scenarios.

There are many different views on the future of smart contract programming languages, broadly speaking, there are four types:

- There is no need for a Turing-complete smart contract language, Bitcoin's script is enough. Without a Turing-complete smart contract language, it is difficult to achieve universal arbitration capabilities and will limit the application scenarios of the chain. This can be seen in my previous article "Opening the 'Three Locks' of Bitcoin Smart Contracts."

- There is no need for a new smart contract language, existing programming languages are enough, as we have analyzed above.

- A Turing-complete smart contract language is needed, but the application scenario is limited to the chain, similar to stored procedure scripts in database. This is the view of most current smart contract developers.

- Smart contract programming languages will be promoted to other scenarios and ultimately become a universal programming language.

The last one can be called the maximalist of smart contract languages, and I personally hold this view.

The reason is simple: in the Web3 world, whether it's a game or other applications, there needs to be a digital dispute arbitration solution if there is a dispute. The key technology points of blockchain and smart contracts are about proof of state and computation, and the arbitration mechanisms developed in this field can be used in more general scenarios. When a user installs an application, is concerned about its security, and wants the application to provide proof of state and computation, that is when the application developer must choose to use smart contracts to implement the core logic of the application.

Summary

This article explains Move's attempts to implement on-chain smart contracts and the challenges faced by current smart contracts in terms of dependency and composability. Based on these attempts, the article also explores the potential for Move ecosystem building.

Afterword: When writing this article, the Rooch project had not yet been created, but ideas about layered solution and DApp building had been brewing in my mind for a long time. Rooch is an answer to how to use Move to build DApp beyond DeFi. For more details, please see the article "The Modular Evolution of Rollup Layer2 (opens in a new tab)".

Links

- https://github.com/move-language/move (opens in a new tab) The new repository of the Move project

- awesome-move: Code and content from the Move community (opens in a new tab)

- Soulbound (opens in a new tab) Vitalik's article about NFT Soulbound

- SIP22 NFT (opens in a new tab) Starcoin's NFT standard, including the explanation of IdentifierNFT

- Unlocking the "Three Locks" of Bitcoin Smart Contracts (jolestar.com) (opens in a new tab)